By Erik Peper, PhD

Table of Contents

Today, forty percent of adults and eighty percent of teens report experiencing significant visual symptoms (eyestrain, blurry vision, dry eyes, headaches, and exhaustion) during and immediately after viewing electronic displays. These “technology-associated overuse” symptoms are often labeled as digital eyestrain or computer vision syndrome (Rosenfield, 2016; Randolph & Cohn, 2017). Even our distant vision may be affected—after working in front of a screen for hours, the world looks blurry.

At the same time, we may experience an increase in neck, shoulder, and back discomfort. These symptoms increase as we spend more hours looking at computer screens, laptops, tablets, e-readers, gaming consoles, and cellphones for work, taking online classes, watching streaming videos for entertainment, and keeping connected with friends and family (Borhany et al, 2018; Turgut, 2018; Jensen et al, 2002).

Eye, head, neck, shoulder, and back discomfort are partly the result of sitting too long in the same position and attending to the screen without taking short physical and vision breaks, moving our bodies and looking at far objects every 20 minutes or so. The obvious question is, “Why do we stare at and are captured by, the screen?” Two answers are typical: (1) we like the content of what is on the screen; and, (2) we feel compelled to watch the rapidly changing visual scenes.

From an evolutionary perspective, our sense of vision (and hearing) evolved to identify predators who were hunting us, or to search for prey so we could have a nice meal. Attending to fast moving visual changes is linked to our survival. We are unaware that our adaptive behavior of attending to visual or auditory signals activates the same physiological response patterns that were once successful for humans to survive—evading predators, identifying food, and discriminating between friend or foe. The large and small screen (and speakers) with their attention grabbing content and notifications have become an evolutionary trap that may lead to a reduction in health and fitness (Peper, Harvey & Faass, 2020).

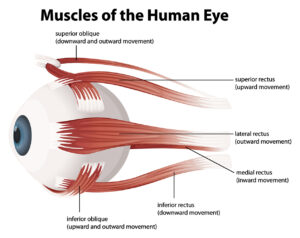

To be able to see the screen, the eyes need to converge and accommodate. To converge, the extraocular muscles of the eyes tighten; to focus (accommodation), the ciliary muscles around the lens tighten to increase the curvature of the lens. This muscle tension is held constant as long as we look at the screen. Overuse of these muscles results is near-vision stress that contributes to computer-vision syndrome, the development of myopia in younger people, and other technology-associated overuse syndromes (Sherwin et al, 2012; Enthoven et al, 2020).

Near-Vision Stress

Continually overworking the visual muscles related to convergences increases tension and contributes to eyestrain. While looking at the screen, the eye muscles seldom have the chance to relax. To function effectively, muscles need to relax /regenerate after momentary tightening. For the eye muscles to relax, they need to look at the far distance–preferably objects green in color.

As stated earlier, the process of distant vision occurs by relaxing the extraocular muscles to allow the eyes to diverge along with relaxing the ciliary muscle to allow the lens to flatten. In our digital age, where screens of all sizes are ubiquitous, distant vision is often limited to the nearby walls behind a screen or desk, which results in keeping the focus on nearby objects and maintaining muscular tension in the eyes.

As we evolved, we continuously alternated between looking at the far distance as well as nearby areas for food sources and signals indicating danger. If we did not look close and far, we would not know if a predator was ready to attack us. Today we tend to be captured by the screens.

Arguably, all media content is designed to capture our attention, such as data entry tasks required for employment, streaming videos for entertainment, reading and answering emails, playing e-games, responding to text notifications, looking at Instagram and Snapchat photos and Tiktok videos, scanning Tweets and using social media accounts such as Facebook. We are unaware of the symptoms of visual stress until we experience symptoms.

To illustrate the physiological process that covertly occurs during convergence and accommodation, you can do the following exercise:

Sit comfortably and lift your right knee a few inches up so that the foot is an inch above the floor. Keep holding it in this position for a minute…. Now let go and relax your leg.

A minute might have seemed like a very long time and you may have started to feel some discomfort in the muscles of your hip. Most likely, you observed that when you held your knee up, you most likely held your breath and tightened your neck and back. Moreover, to do this for more than a few minutes would be very challenging.

Now, lift your knee up again and notice the automatic patterns that are happening in your body… For muscles to regenerate they need momentary relaxation which allows blood flow and lymph flow to occur. By alternately tensing and relaxing muscles, they can work more easily for longer periods of time without experiencing fatigue and discomfort (eg, we can hike for hours but can only lift our knee for a few minutes).

Solutions to Relax the Eyes and Reduce Eyestrain

You can reestablish the healthy evolutionary pattern of alternately looking at far and near distances to reduce eyestrain by doing such things as:

- Look out through a window at a distant tree for a moment after reading an email or clicking link.

- Look up and at the far distance each time you have finished reading a page or turn the page over.

- Rest and regenerate your eyes with palming. (While sitting upright, place a pillow or other supports under our elbows so that your hands can cover your closed eyes without tensing the neck and shoulders.

Cup the hands so that there is no pressure on your eyeballs, allow the base of the hands to touch the cheeks while the fingers are interlaced and resting your forehead.

Close your eyes and imagine seeing blackness. Breathe slowly and diaphragmatically while feeling the warmth of the palms soothing the eyes. Feel your shoulders, head, and eyes relaxing. Palm for 5 minutes while breathing at about six breaths per minute through your nose. Then stretch and go back to work.)

Palming is one of the many practices that improves vision. For a comprehensive perspective and pragmatic exercises to reduce eyestrain, maintain, and improve vision, see the superb book by Meir Schneider, PhD, LMT, Vision for Life, Revised Edition: Ten Steps to Natural Eyesight Improvement.

Increased Sympathetic Arousal

Seeing the changing stimuli on the screen evokes visual attention and increases sympathetic nervous-system arousal. In addition, many people automatically hold their breath when they see novel visual stimuli or hear auditory signals since they trigger a defense or orienting response. At the same time, without awareness, we may tighten our neck and shoulder muscles as we bring our nose literally to the screen.

As we attend to and concentrate to see what is on the screen, our blinking rate decreases significantly. From an evolutionary perspective, an unexpected movement in the periphery could be a snake, a predator, a friend, or foe and the body responds by getting ready: freeze, fight, or flight. We still react with the same survival responses while looking at screens.

Some of the physiological reactions that occur include breath holding or shallow breathing. These often occur the moment we receive a text notification, begin concentrating and respond to the messages, or start typing or mousing. Without awareness, we activate the freeze, flight, and fight response. By breath holding or shallow breathing, we reduce or limit our body movements, effectively becoming a non-moving object, which brings us back to survival mode as a still body is more difficult to see by many animal predators. In addition, during breath holding, hearing becomes more acute because breathing noises are effectively reduced or eliminated.

Another physiological reaction is inhibition of blinking. When we blink it is a movement signal that in earlier survival times could give away our position. In addition, the moment we blink we become temporarily blind and cannot see what a predator could be doing next.

Finally there is increased neck, shoulder, and back tension. The body is getting ready for a defensive fight or avoidance flight.

Experience some of these automatic physiological responses described above by doing the following two exercises.

- Eye movement neck connection: While sitting up and looking at the screen, place your fingers on the back of the neck on either side of the cervical spine just below the junction where the spine meets the skull. Feel the muscles of neck along the spine where they are attaching to the skull. Now quickly, with your eyes, look to the extreme right and then to the extreme left. Repeat looking back and forth with the eyes two or three times. What did you observe? Most likely, when you looked to the extreme right, you could feel the right neck muscles slightly tightening and when you looked the extreme left, the left neck muscles slightly tightening. In addition, you may have held your breath when you looked back and forth.

- Focus and neck connection: While sitting up and looking at the screen, place your fingers on the back of the neck as you did before. Now focus intently on the smallest size print or graphic details on the screen. Really focus and concentrate on it and look at all the details. What did you observe? Most likely, when you focused on the text, you brought your head slightly forward and closer to the screen, felt your neck muscles tighten, and possibly held your breath or started to breathe shallowly. As you concentrated, the automatic increase in arousal, along with the neck and shoulder tension and reduced blinking contributed to developing discomfort. This can become more pronounced after looking at detailed figures, numerical data, characters and small images for hours (Peper, Harvey & Tylova, 2006; Peper & Harvey, 2008; Waderich et al, 2013).

Staying alert, scanning, and reacting to the images on a computer screen or notifications from text messages, can become exhausting. in the past, we scanned the landscape, looking for information that will help us survive (predators, food sources, friends, or foes); however, today, we react to the changing visual stimuli on the screen. The computer displays and notifications have become evolutionary traps since they evoke these previously adaptive response patterns that allowed us to survive.

Awareness As a Solution

These response patterns occur mostly without awareness until we experience discomfort. Fortunately, we can become aware of our body’s reactions with physiological monitoring, which makes the invisible visible as shown in the figure below (Peper, Harvey & Faass, 2020).

As is shown in the charted results of monitoring with biofeedback feedback devices, representative physiological patterns that occur when working at a computer, laptop, tablet, or cellphone are unnecessary neck and shoulder tension, shallow rapid breathing, and an increase in heart rate during data entry. Even when the person is resting their hands on the keyboard, forearm muscle tension, breathing, and heart rate increased.

Moreover, muscle tension in the neck and shoulder region also increased, even when those muscles were not needed for data entry task. This unnecessary tension and shallow breathing contributes to exhaustion and discomfort (Peper, Harvey & Faass, 2020).

With biofeedback training, the person can learn to become aware and control these dysfunctional patterns and prevent discomfort (Peper & Gibney, 2006; Peper et, 2003).

However, without access to biofeedback monitoring, it’s wise to assume that you respond similarly while working or using devices with keyboards and screens. Thus, to prevent discomfort and improve health and performance, it’s best to implement the following.

- Practice breathing lower and slower to reduce sympathetic activation. Every few minutes remember to breathe slowly in and out through the nose. See the following blogs for more detailed instructions:

- Blink many times. Blink each time you click on a link, after typing a paragraph, or after entering a few numbers.

- Get up, move, stretch, and wiggle.

- Every few minutes do a small movement such as rotating your shoulders, or dropping your hands to your lap.

- Every twenty minutes get up, stretch, and walk around to reduce the chronic muscle tension. Install the free Stretch Break software on your computer or laptop to remind you to stretch… it shows you how. Download a free version from: https://stretchbreak.com/

- Use small portable muscle biofeedback devices to learn awareness of the covert muscle tension and how to work without unnecessary muscle tension. For detailed training procedures see the free downloadable book by Erik Peper and Katherine Gibney, Muscle Biofeedback at the Computer- A Manual to Prevent Repetitive Strain Injury (RSI) by Taking the Guesswork out of Assessment, Monitoring and Training.

—

The above is adapted by permission from: Peper, E, Harvey, R & Faass, N (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. See TechStress for a comprehensive overview based on an evolutionary perspective that explains why TechStress develops, why digital addiction occurs, and what can be done to prevent discomfort and improve health and performance.

Erik Peper, PhD, is Professor of Holistic Health, Institute for Holistic Health, San Francisco State University, and is president of the Biofeedback Federation of Europe. He maintains a private practice (www.biofeedbackhealth.org) and loves exploring new ways of empowering people to optimize health and wellness.

References

- Borhany, T, Shahid, et al (2018). “Musculoskeletal problems in frequent computer and internet users.” Journal of family medicine and primary care, 7(2), 337–339.

- Enthoven, C A, Tideman, WL, Roel of Polling, RJ,Yang-Huang, J, Raat, H, & Klaver, CCW (2020). “The impact of computer use on myopia development in childhood: The Generation R study.” Preventive Medicine, 132, 105988.

- Jensen, C, Finsen, L, Sogaard, K & Christensen, H (2002). “Musculoskeletal symptoms and duration of computer and mouse use,” International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 30(4-5), 265-275.

- Peper, E & Gibney, K (2006). “Muscle Biofeedback at the Computer- A Manual to Prevent Repetitive Strain Injury (RSI) by Taking the Guesswork out of Assessment, Monitoring and Training.” The Biofeedback Federation of Europe. Download free PDF version of the book: http://bfe.org/helping-clients-who-are-working-from-home/

- Peper, E & Harvey, R (2008). “From technostress to technohealth.” Japanese Journal of Biofeedback Research, 35(2), 107-114.

- Peper, E, Harvey, R & Faass, N (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

- Peper, E, Harvey, R & Tylova, H (2006). “Stress protocol for assessing computer related disorders.” Biofeedback. 34(2), 57-62.

- Peper, E, Wilson, VS, Gibney, KH, Huber, K, Harvey, R & Shumay. (2003). “The Integration of Electromyography (sEMG) at the Workstation: Assessment, Treatment and Prevention of Repetitive Strain Injury (RSI).” Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 28 (2), 167-182.

- Randolph, SA & Cohn, A (2017). “Computer vision syndrome.” Workplace, Health and Safety, 65(7), 328.

- Rosenfield, M (2016). “Computer vision syndrome (a.k.a. digital eye strain).” Optometry in Practice, 17(1), 1 1 – 10.

- Schneider, M (2016). Vision for Life, Revised Edition: Ten Steps to Natural Eyesight Improvement. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. https://self-healing.org/shop/books/vision-for-life-2nd-ed

- Sherwin, JC, Reacher, MH, Keogh, RH, Khawaja, AP, Mackey, DA, & Foster, PJ (2012). “The association between time spent outdoors and myopia in children and adolescents.” Ophthalmology, 119(10), 2141-2151.

- Turgut, B (2018). “Ocular Ergonomics for the Computer Vision Syndrome.” Journal Eye and Vision, 1(2).

- Waderich, K, Peper, E, Harvey, R, & Sara Sutter (2013). “The psychophysiology of contemporary information technologies-Tablets and smart phones can be a pain in the neck.” Presented at the 44st Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. Portland, OR.